Ethiopia’s Wounds Are Too Fresh for Military Reorganization

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed wants to reorganize the military into a centralized force but meets fierce opposition from ethnic factions.

In Ethiopia, tensions have been rising since last Thursday when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed called for the reorganization of regional militias into a ‘centralized’ national army/police force. In the Amhara region, the second largest in the country, huge protests erupted across cities and towns as the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) sent heavily armed military and police forces across the region to disarm the Amhara Regional Special Police Force (SPF). According to BBC, arrests of journalists and community organizers in the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, took place in the following days. Curfews have been imposed in the historic city of Gondar in the Amhara region, and deadly clashes between protesters and police are common.

In the Amhara region, people fear that dismantling the local militia in favor of a centralized model will put them in jeopardy, and for good reason — since Prime Minister Abi Ahmed took power, various systematic massacres of the Amhara people have taken place.

Ahmed claims that the reorganization in peacetime is necessary to preserve the strength of the Ethiopian army and prevent future conflicts. He likely seeks to avoid another Tigray War, where the federal government of Ethiopia fought in a bloody two-year conflict against the forces of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

The Amhara, who fought alongside the federal government in the Tigray War until the ceasefire ending fighting last November, are distrustful of the federal government, and are now accusing the Prime Minister of violating the constitution, which allows local regions to maintain their own security forces.

Further conflicts seem inevitable as neither side is backing down; the Amhara SPF forces won’t stand for being disarmed and the ENDF forces are conducting a relentless campaign to disarm them. Efforts from foreign powers to establish peace in Ethiopia have largely been concentrated on mediating talks between the TPLF and the federal government, and not enough of a public outcry has come yet for international mediating of the worsening situation in Amhara.

What is also at stake here are the larger ideas of multiethnic autonomy that the Ethiopian government was founded upon. Respecting ethnic groups’ right to self-determination is not only a core principle of their constitution, but also allowed the country to resolve large-scale conflicts between centralized state and ethnically based liberation fronts into a period of relative stability. The prime minister would be wise to postpone any attempts to reorganize the military at this time, as ongoing conflicts between ethnic groups are open wounds not to be picked at.

Ethiopia: A Brief Overview

Ethiopia at 113 million people is the 13th largest population in the world, and the 2nd largest in Africa. It is the most populated landlocked country in the world. Its capital and most populated city, Addis Ababa, lies on the East African Rift, which splits Ethiopia in two, between the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate. The country is a loose conglomeration of ethnicities that maintain deep cultural, linguistic and religious differences. Christianity had been heavily integrated starting somewhere around the 4th century, and Islam somewhere around the 7th century, with today the nation being split roughly between 2/3rds Christian and 1/3 Islamic. Ethiopian history is scarcely documented but contains some of the oldest pieces of humanity in the world. With the discovery of early hominids such as Lucy and Adri it has become the forefront of paleontology. Ethiopia is also widely credited with being the first to make coffee, so let’s all thank them for that.

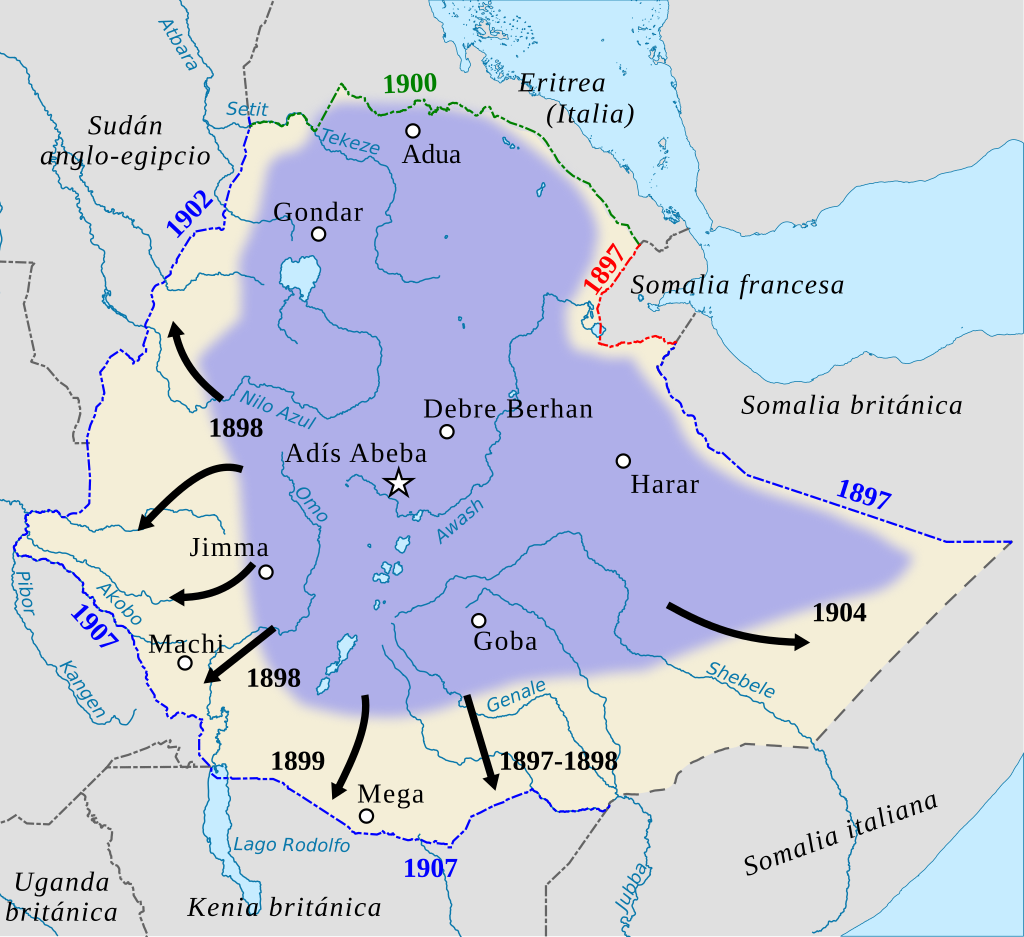

The largest ethnic group in Ethiopia today are the Oromo, a pastoral people with their own language who regulated their political and economic systems activities through a democratic system called Gadaa. The Oromo did not have much of a regional influence and had infrequent moments of ethnic unification. They would not be assimilated into a larger Ethiopian state until Emperor Menelik II set out on a series of campaigns from 1878–1904 to expand his empire. These brutal wars of expansion are largely responsible for the borders of modern Ethiopia today.

Menelik was the son of an Amhara king, a Semitic-speaking ethnic group that is now the second largest ethnic group in Ethiopia. Like many other Amhara leaders, he claimed to be a direct descendant of King Solomon. Beginning in the 1870s, his quest for a greater Ethiopia led him to conquer the regions of the south, east and west. According to legend, his empress chose the site and first founded the city of Addis Ababa, meaning new flower. His conquests to the east, south, and west led him to unify enough forces to fight off the invading Italians in the First Italo-Ethiopian War of 1895-96.

Despite the stark differences of different ethnic groups, uniting forces was the main thing that kept Ethiopians from being the only African country other than Libera to not be conquered by European colonization during the “Scramble for Africa” period. Apart from the brief Italian occupation of Ethiopia in the 1930’s, it has remained largely unconquered form foreign military might. The Ethiopian “imperial” period of emperors ended in 1974 when a military junta known as the Derg overthrew the last emperor. From 1975 to 1991, the Derg ruled as a Marxist-Leninist state. Their rule was rife with famine, civil war, and their own ‘Red Terror’ campaigns, until the Derg collapsed, and a new interim government was formed in 1991.

Bordering Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Kenya, and Djibouti, the country has had a long history of intense border disputes. The Ethiopian-Somali border has long been a strain with Somalia’s constant regime shifts, and a border dispute with Sudan to the West has been brewing as recently as last summer. Perhaps most famously are the long border wars with Eritrea to the north. A thirty-year war of independence was fought between 1961-1991, which Eritrea finally gaining their independence in 1993. Although the two nations reconciled briefly afterwards, further border disputes led to the Eritrean–Ethiopian War of 1998-2000, which was only fully settled in 2018 by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who implemented the peace deal set in motion 18 years before.

Strength (And Weakness) Through Diversity

When the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) rose to power in 1991, they first introduced the idea of ethnic self-determination, going beyond other African governments’ attempts to manage ethnic diversity. At the time, interim president and later Prime Minister Meles Zenawi implemented a policy of ethnic federalism, a system in which the regional units are defined by ethnicity. Every ethnic group has the right to have its own militia, or even secede if specific conditions are met (Article 39 of the constitution). Although these rights are safeguarded in the constitution, it is still the most contested principle in Ethiopian politics. The Ethiopian census lists more than 90 distinct ethnic groups in the country. Furthermore, these ethnic groups are not homogenous in thought or political will, often holding conflicting interests across class, age, and gender lines. All of this, especially the language barriers, have been a challenge to a national Ethiopian identity that past leaders have tried to cultivate.

The country in recent years has been plagued by increasing allegations of apartheid and ethnic war crimes on multiple sides, to a level that constitutes genocide. The current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is of Oromo descent, being the first Oromo head of state. The Oromo have their own narrative about oppression and subjugation during Ethiopia’s imperial period, as well as their lack of political representation after years of TPLF-EPRDF domination. Critics will downplay Oromo subjugation by pointing to the fact that the imperial period ended in 1974, or that for the past 5 years, the Oromo have been seated at the head of government.

After the Tigray War from 2020-2022, the TPLF, which along with the EPRDF helped found the country under a new constitution in 1991, was designated as a terrorist group. Barred from participating in the federal government, the TPLF represents an ethnic region that is populated by 7 million people, and there is still a struggle to properly represent them in government after the conflict. The Eritreans helped the Ethiopian federal government fight the Tigray war, where a long and bitter feud with the Tigray people was again able to express itself.

But perhaps presently the loudest claim to oppression is the Amhara people. Amhara elites were widely dominant as the ruling class for most of the last century. This allowed a diverse identity to be cultivated among the Amhara, where they saw themselves more as Ethiopians than as Amhara. So, when other Ethiopian ethnicities gained power from the birth of the transitional government in 1991, many were hesitant to adapt an ethnic-based political system. In recent years there’s been a shift to a greater sense of Amhara nationalism, driven by the rise of an increasing sense of alienation and subjugation from other ethnic groups.

Consolidation of Power

When Prime Minister Abiy took power in 2018, many Amhara initially supported the new government and welcomed it as a changing of the guard from the old TPLF-EPRDF domination. The Amhara participation in the Tigray war also brought a sense of reprieve between ethnic tensions, but that was short-lived. The new government was thought to have handled the Amhara massacres in the Oromia region poorly. The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) was blamed for the attacks, which the OLA has denied. Optically, the Amhara people blame the federal government. They see the Oromia led administration as taking measures to gradually take over Addis Ababa, which also intensifies the view of hostile takeover by new administration. Amhara genocide is an extensive and still very modern topic.

So, when Abiy’s administrations wants to restructure the military, forcing the Amhara to hand over their guns and join the national government, the Amhara have good reason to resist giving up their autonomy. In a recent parliament appearance, he called for Amhara and Oromo people to “reduce the hatred”, to “calm down and engage in dialogue”. Although these are the right things that a leader should be saying at such a contentious time, they were followed up by the divisive announcement that all ethnicities will abandon their well-structured security forces, some built up to the point they resemble small armies. Although this is a sensible long-term solution, it comes at a time when tensions are at an all-time high, and Abiy is better off at the very least, delaying any attempts at consolidation until the majority of Amhara’s favor it.

The last thing Ethiopia needs is to burst at the seams again. Leaders should avoid picking at any wounds that further inflame sectarian conflict. “There is no lasting benefit from a temporary solution!" reads the caption of a lengthy statement Abiy put out about military reconfiguration on Twitter. The statement threatens those who do not comply and focuses on the strength of a unified national military. Based on the comments and surveying the general atmosphere of Ethiopian social media, it just makes him look more out of touch with his people.

What the government ought to be conveying is an adherence to the foundational principles of the Ethiopian constitution: respecting the self determination of different ethnicities and protecting their right to self-security. Restructuring the identity of the Ethiopian people to once again embrace an Ethiopian identity, even within the context of your own ethnic background — even if that means criticizing your own ethnic political structure that bolstered you into power. Now is not the time for forced military consolidation, as it will not bring about the multinational unity that Abiy allegedly hopes to achieve. The reason Ethiopia has been resilient to outside parties is its ability to put aside ethnic differences and unite as a greater nation, but this must be done willingly, at opportune times, with more concessions, discourse, and respect for ethnic differences.

Physically speaking, we can not separate. We can not remove our respective sections from each other nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other, but the different parts of our country can not do this. They can not but remain face to face, and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. Is it possible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than before? Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens than laws can among friends? Suppose you go to war, you can not fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you. - Abraham Lincoln [First Inaugural Address]

Very good article as a beginner ! Please keep up! I would be happy if you include that TPLF is mobilizing militants towards Amhara region at the moment. And Abiy and his administration is working day and night for oromo region independence for this reason they have to dismantled all other regional forces except oromo regional forces.

Anyways thank you so much !