Iran-Saudi Agreement: A Tale of Two Approaches

China is mending ties and fostering diplomacy while the U.S. policy of bribery and subversion fumbles, highlighting the absurdity of Washington's approach.

Part of diplomacy is to open different definitions of self-interest. - Hillary Clinton

The new China-mediated Saudi-Iran deal makes one reevaluate decades of United States policy towards the Saudi government. So much of Washington’s approach to the region has been shaped by jumping through hoops to maintain good relations with the House of Saud, or finding ways to undermine and subvert the Ayatollah. With Beijing swooping in to broker rapprochement between the nations, Washington’s wayward and perverse tactics seem illogical to the point of absurdity.

The deal reopens relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, establishing embassies in each other’s countries within a period of two months. The countries had previously cut off diplomatic ties in 2016 when protesters set ablaze the Saudi embassy in Tehran in response the execution of beloved Shia cleric Nimr Al-Nimr:

Although that incident was the straw that broke the camel’s back, the divide between the two dominant Muslim nations runs much deeper. The reconciliation is remarkable in that it transcends ethnic, religious, and political conflicts that divide the region, sometimes culminating in a cold war-style conflict, complete with an arms race and proxy wars over regional power and influence. But it goes further than just reestablishment of diplomatic ties — the Saudis have pledged to not fund media outlets that destabilize Iran and the nations promise to work together to end the civil war in Yemen, something unthinkable just a few years ago. The other remarkable fact is that China, in short order, has been able to accomplish more for peace and stability in the region than America has been able to do in decades of exerting its influence over the Middle East.

The contrast of Beijing’s successes to Washington’s failures highlights the different approaches between the two superpowers. America’s long history with Tehran consists of engaging in extensive proxy wars, covert operations, and oppressive sanctions — often for the benefit of Israeli or Saudi interests, even when it goes against the wants and needs of Americans. On the other hand, Washington has ignored numerous human rights violations, usurped the will of congress, and gone against the interests of their own citizens for leverage with Riyadh. Beijing had done things the right way — maintained relations with two nations and negotiated a diplomatic settlement. Also, at the right time — the rapprochement comes when the U.S. was attempting to negotiate normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel, which the deal mediated by China between Tehran and Riyadh could complicate, thus further diminishing Washington’s influence in the region.

Washington’s strict sanctions policy against Tehran was intended to pressure Iran to abandon its nuclear weapons program, instead the sanctions have only backfired, with Iran recently enriching uranium close to weapons-grade levels as Biden administration officials failed to negotiate a new Iran Nuclear deal when they took office in January 2021. Before leaving office, the Trump administration had listed Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist organization as a means of preventing Biden or any future president from renegotiating the deal. Biden's insistence on not delisting the IRGC as a terror group unless Iran made additional concessions became a non-starter that prevented a renegotiation of the deal. This made the moderates in Iran who favored working with the Americans look naïve. “You can’t negotiate with them” was the take home message that contributed at least in part to the election of hardliner Ebrahim Raisi as Iran's new president, who has no trust in talking with the Americans.

We had in fact, obstructed the normalization of diplomatic ties between the countries. Contrary to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s claims that Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani was planning an attack on American bases in the region, he was on his way to negotiate a rapprochement deal with the Saudis when he was assassinated in Iraq, according to Iraqi Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi. Pompeo knew that this was a lie, and had already had plans to assassinate Soleimani months prior. Such a plan of rapprochement would threaten an anti-Iran axis of Israel and regional Arab states against Iran, as the recent diplomatic ties between the two nations have ostensibly hindered.

U.S.-Saudi History: Converging Interests

The partnership between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia predates World War II, when in 1933 California-based Standard Oil was allowed to explore Saudi lands for undiscovered petroleum. During the war, when the axis powers bombed Saudi oil fields, crippling production, they looked for a country to provide security to the kingdom in exchange for access to their abundant oil reserves. They found their candidate in Washington. In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that "the defense of Saudi Arabia is vital to the defense of the United States." With the exception of an oil embargo in the 1970s, this “security for oil” exchange was the cornerstone of U.S.-Saudi relations. This bond was further strengthened by the anti-communist sentiment in the two countries, when both backed the Arab Mujahideen in Afghanistan fighting the Soviets. Additionally, soon after the 1979 Islamic Shia Revolution took place in Iran it gave Riyadh and Washington a common enemy, where interests naturally converged.

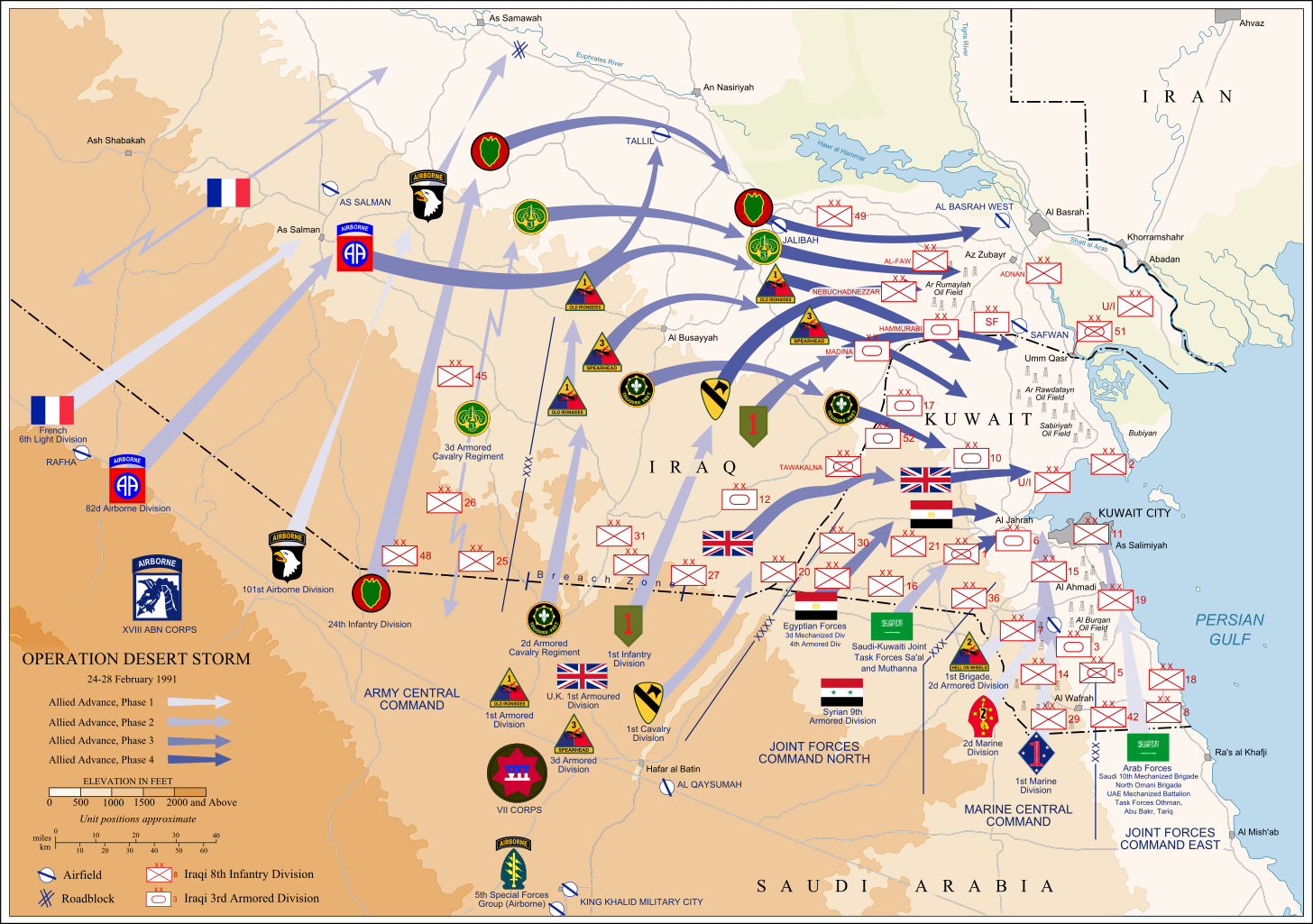

This partnership was at its strongest during the Regan and Bush years when they had yet another common enemy to confront. In the 80’s, Saddam Hussein, leader of the Iraqi Baathist party, had been lent 28 billion dollars by the Saudis in his grueling war against Iran, which he had no intentions of paying back. He claimed he was doing the Saudis a favor by doing the fighting against their enemy in Tehran for them. When Hussein used his Iraqi army to invade Kuwait in August of 1990 he became in striking distance of Saudi oil fields, threatening the worlds oil reserves and then a grave security concern for the kingdom. George H. W. Bush responded by launching a “wholly defense” troop build up in Saudi Arabia to prevent against an invasion from Iraq. Between August of 1990 and January of 1991, 500,000 American troops poured into Saudi territory and the campaign became offensive in Operation Desert Storm.

The American military bases on Saudi territory would put a strain on their relationship to the Muslim world. Occupation of holy ground was considered sacrilegious by jihadists, and it inspired Osama Bid Laden to declare his first fatwa against the United States, entitled: Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places. Proof that it was in fact not because they “hate us for our freedoms.” When the September 11th, 2001 attacks took place by Al-Qaeda, consternation by Americans about the entire Muslim world was apparent. 15 of the 19 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia, and the mastermind Bin Laden himself was the son of a Saudi Arabian billionaire. Although he had his citizenship revoked in 1994, many thought he chose mostly Saudi hijackers so he could put a strain on U.S.-Saudi relations. But if that was a goal, it backfired, at least temporarily. The Saudis worked with the Americans on counter-terrorism operations. Even as Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman publicly protested the Iraq war, his regime covertly supported the campaign, allowing widespread military operations to take place from the secret American bases there.

Appeasement Politics

The Saudis, like the Americans thought of Saddam as a thorn in their side and were happy to get rid of him. But when the Sunni leadership in Iraq was in shambles it strengthened the Shiite Iran friendly majority in the country, and the architects of the war began to realize their mistake. By late 2006, it was becoming clear the victor in the Middle East from Washington’s campaign in Iraq had been Iran. As there was growing talk among the state department to withdraw from the region as well as waning public support for the war, the Saudis had urged Washington not to pull out. If the Americans leave, than the Saudis would have to take matters into their own hands and start backing the Sunni minority, even if those people are hostile to American forces. While it’s impossible to say the extent to which the U.S. decision to shift targets midway through the Iraq war was influenced by the Saudis, it was certainly in their interest, even though it meant fighting the same factions we spent years helping.

Changing Presidents world hardly change our tone with the monarchy state. When Obama got into office, he signed a record 60 billion dollar arms deal with the Saudis in an effort to isolate Iran. Officials from both sides of the aisle questioned how such an arms deal was in our national interest. A letter sent to the president questioning the deal got 198 signatures from congress. Instead of pausing the deal, he snuck the sale under the radar just as congress was leaving for the midterms. Thomas Lippman, member of the Council on Foreign Relations said "part of what the [Obama] administration is doing, is to convince the Saudis that we can take care of their security concerns without them getting nuclear." Yet, when it has been suggested that we don’t arm the Saudis for sharing responsibility in any war crimes they commit, the excuse for doing so is, “if we don’t do it, somebody else will sell them the weapons.”

In 2011 while the Obama administration set off on their campaigns in Syria and Libya, warning of human rights abuses, an Amnesty International report spoke of a “new wave of repression” in the kingdom. With hundreds of arrests and multiple public beheadings, the administration stayed peculiarly quiet on the human rights violations there, despite dozens of NGOs demanding that Obama hold the same standard for the Saudis that he is holding for the other enemies of the empire. Instead, when King Abdullah died, Obama cut his trip to India short to travel to the kingdom and praise the Monarch for his upstanding character.

Perhaps Washington’s biggest embarrassment comes from all of the now vain efforts to appease and coddle the House of Saud into loyalty. In 2015, after negotiating the Iran deal, we agreed to help the new Saudi Prince wage his genocidal war against the allegedly Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen in order to stay in the royal families’ good graces. “We’re doing this not because we think it would be good for Yemen policy; we’re doing it because we think it’s good for U.S.-Saudi relations,” said Ilan Goldenberg, a former Obama administration official.

Previously, many officers at the U.S. Special Operations Command had favored the Houthis as they provided a counter to Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The notion that they were an Iranian proxy was used as a pretext for the war, but it never had any validity. They seldom got weapons from and never took orders from Tehran. In fact, it was the Saudi campaign against them brought the groups closer together. As Trita Parsi at Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft describes: “Had the Saudis not invaded, Tehran would not even have been able to deepen its relations with the Yemeni group.” Worst of all, the campaign in Yemen contribute to strengthening and enriching AQAP while Saudi war planes bombed school centers, hospitals and food production centers. This was the level of appeasement that three U.S. administrations were willing to go to: genocide and empowering Al Qaeda — the butchers of New York.

But the benefit for sacrificing the people of Yemen was supposed to be Saudi loyalty and guarantees on cheap oil, at least for a while. Instead, the Saudi’s slashed oil production when the Biden administration thought they struck a deal with them last October, leaving their heads scratching over the outcome. They have misread Saudi leadership. The Saudi Energy Ministry said “the decisions of OPEC Plus are reached by the consensus of all members and determined solely by market fundamentals, not politics.” This attitude is shared by the heads of government, and plays into Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s decision of rapprochement with Iran. He is clearly not motivated by brides and good gestures, sectarian conflicts between Sunnis and Shiites, or Arabs and Persians, but by his own countries self interest in the way he finds most beneficial. This is a painful truth for Washington officials, who have shaped their foreign policy around staying in the good graces of the House of Saud, only for them to normalize relations with country public enemy number one.

Much more could be said about all of the times Washington coddled the Saudis. I don’t think anything will be learned from American officials from this. We will revert back to our same old tactics:

Another lesson from this is the economic tide of countries like Syria, Iran, and Russia reintegrating with the national community cannot be contained, only postponed. The U.S. led sanctions on the imposed countries are challenged by a growing multi-polar world order that only hinders economic opportunity. Ultimately, nations of tens or hundreds of millions of people have cultures and populations that are bigger than any one leader or government. Any long-term strategy to isolate or contain such an outgrowth rather than assimilate them into the national order is misguided. If one power structure doesn’t make the best of those resources, manufacturing capabilities and populace within the country, another will. Russia accelerating imports to India and Iran making agricultural and industrial deals China are examples of this. Such a need to have a geo-strategic advantage has barred the U.S. from reaping the benefits of these emerging powers. Washington thinks they are staying ahead of the game by political tactics of appeasement and subversion, when in reality, that is the very reason they are falling behind.