The Rape of West Papua

A corporate-state syndicate created over half a century ago continues to wreck havoc on Indonesia's biggest island.

“For a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.”

-Frantz Omar Fanon, [The Wretched of the Earth]

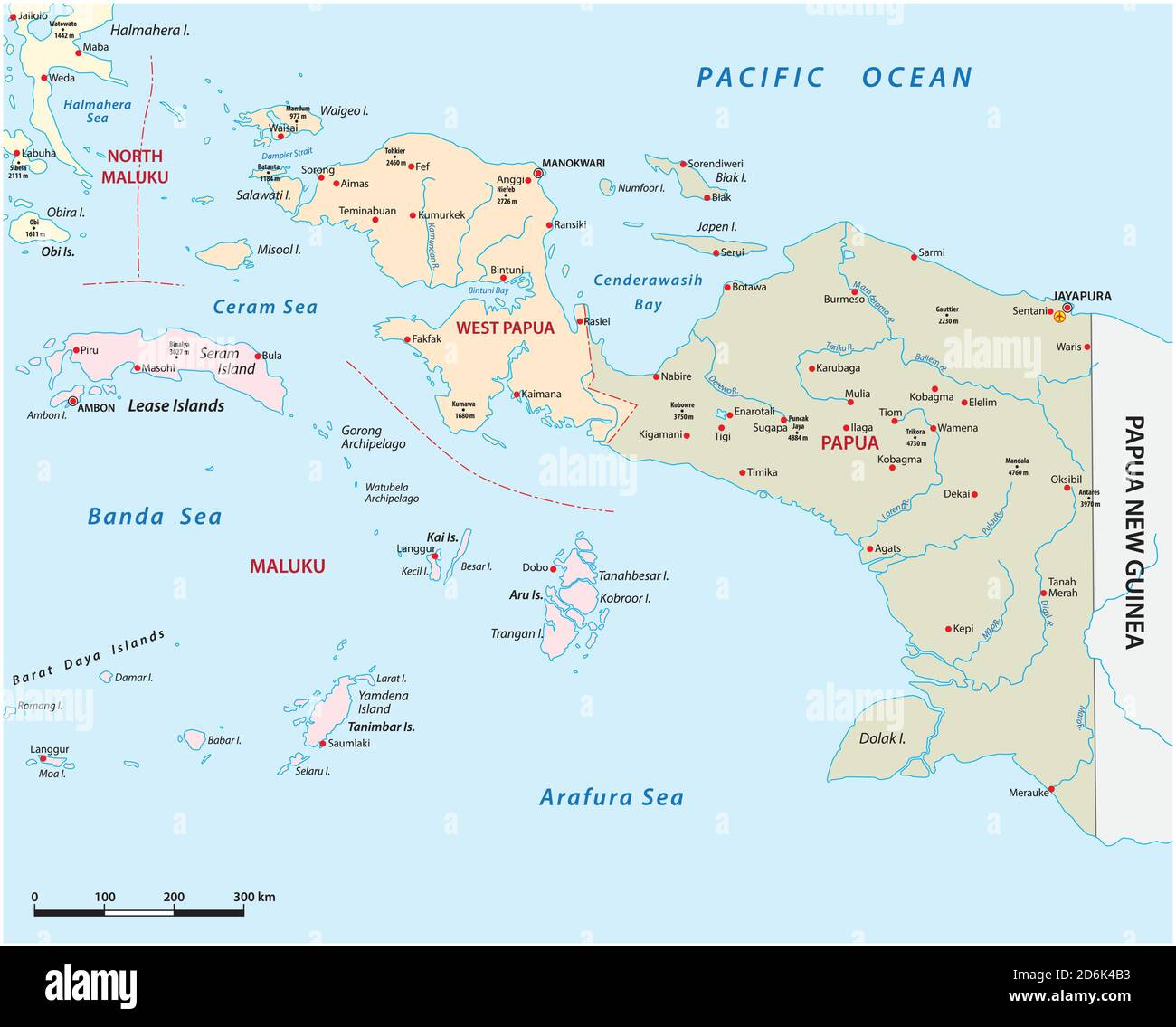

Located on the western half of the island of New Guinea lies a region that is a part of Indonesia, known as West Papua. The terminology can be confusing, because West Papua is a province connected to mainland Papua, but also used to refer to the part of the island of New Guinea that Indonesia controls. Up until recently, there was only the provinces of West Papua and Papua (as shown on the map above), but last year the Indonesian government passed a contentious law to divide the region up into several more provinces. Some believe this was done so that the indigenous people of Papua would have more trouble creating united political front — more on that later. For clarity, I will use the term West Papua to apply to the provinces of Central Papua, Highland Papua, Papua, South Papua, Southwest Papua, and West Papua.

West Papua boasts a remarkable and diverse ecology, characterized by its pristine rainforests, stunning coral reefs, and millions of hectares of unique wildlife. The Papua province is the 3rd largest rainforest on Earth, behind the Amazon and the Congo, but because of its relative isolation, it contains many species not found anywhere else on Earth—including marsupials like the black cuscus or the tree kangaroo species, a stunning array of orchids and among the most biodiverse marine life in the world. It is also home to over 250 distinct ethnic groups with different languages and social structures, with deep connections to the land. Because of its remoteness, and vast wilderness, it is one of the few places left has remained largely untouched by modern man. Until recently.

Dutch New Guinea, To Independence, To Annexation

The Dutch had a presence in Indonesia since the late 16th century, Indonesia was a Dutch colony known as the Dutch East Indies, providing spices and cash crops in the 19th and 20th centuries. When Indonesia officially declared its independence from the Dutch in 1949, West Papua played no role in the revolution and did not join the country. This is in part because the Dutch recognized the ethnic and geographic differences of West Papua from the bulk of Indonesians. Papua would remain a Dutch colony until 1961, when the growing independence movement for West Papua would gain steam at a time when decolonization gained momentum around the world. West Papua held congress and voted for independence, and raise the flag of the Morning Star—the official flag of the secessionist movement in West Papua today. A flag that is banned in Indonesia.

The dream was short lived. At this time, the Indonesian government was growing increasingly more confrontational with the Dutch. Dutch capital remaining in Indonesia after independence was threated with nationalization, and Indonesia wanted to oust all Dutch influence in the region with direct confrontation, including a territorial war on West New Guinea. Indonesia under president Sukarno regarded West Papua as an intrinsic part of the country on the basis that it was the successor state to the Dutch East Indies, and therefore should be a part of his state. On top of lots of military posturing, the Indonesian government launched a press campaign to talk of human rights abuses by the Dutch in the region. Reports claimed that Papuans were being “mercilessly persecuted” and “massacred”, which the Dutch officials denied. Neither the West Papua press, nor the foreign independent journalists in the area could confirm Indonesian reports. It was propaganda to turn the West Papuans toward Indonesia.

In order to secure military support for the invasion of West Papua, the Indonesian Government under General Nasution visited Moscow in search of an arms deal. This was highly alarming to the US during the height of the cold war, where they feared Indonesia creating closer ties with the Soviet Union would push the country towards communism. In April 1962, John F Kennedy sent a secret letter to the Prime Minister of the Netherlands urging them to not respect West Papua independence and hand over West Papua to Indonesia. This was Kennedy’s thinking:

If the Indonesian Army were committed to all out war against The Netherlands, the moderate elements within the Army and the country would be quickly eliminated, leaving a clear field for communist intervention. If Indonesia were to succumb to communism in these circumstances, the whole non-communist position in Viet-Nam, Thailand, and Malaya would be in grave peril, and as you know these are areas in which we in the United States have heavy commitments and burdens.

The Netherlands position, as we understand it, is that you wish to withdraw from the territory of West New Guinea and that you have no objection to this territory eventually passing to the control of Indonesia. However, The Netherlands Government has committed itself to the Papuan leadership to assure those Papuans of the right to determine their future political status. The Indonesians, on the other hand, have informed us that they desire direct transfer of administration to them but they are willing to arrange for the Papuan people to express their political desires at some future time.

The outcome of this foreign pressure was the New York Agreement, signed on August 15, 1962. This agreement stipulated that West Papua would be transferred to Indonesia under a temporary administration called the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA). The transfer was to take place by May 1, 1963. The West Papuans did not have a say in the matter. UNTEA was established to oversee the transition period and prepare West Papua for a vote on its political future. The Papuan people, who predominantly favored independence, were largely excluded from the decision-making process.

In 1969, a referendum called the Act of Free Choice (or "Pepera") was held under Indonesian supervision and overseen by the UN. Ostensibly, Papuans had their chance to exercise their right to self-determination. But the Indonesian Government had other plans. The Papuans were seen as too ‘primitive’ to handle democracy, so only 1,026 representatives handpicked by the military were allowed to participate. There is very credible evidence that these men were bribed and threatened, and unanimously all 1026 voted to integrate West Papua into Indonesia. It clearly did not reflect the view of Papuans who just a few years earlier had voted for their independence. The Papuans now call this event the “Act of No Choice.” It remains one of the most shameful events in the history of the UN.

Freeport-McMoRan Saga

Beyond its position in the larger geopolitical struggle of the cold war, there was another reason for foreign interest in West Papua. In 1936, Dutch Geologist Jean Jacques Dozy discovered a black rock with greenish coloring and speculated that it was the site of gold and copper deposits. He published a paper, but it received little attention for the next twenty years. The Dozy report was picked up by geologist Forbes Wilson, vice president of the Freeport Minerals Company, later known as Freeport-McMoRan. In the mid 1960’s before the Act of Free Choice, when West Papua was under temporary control of Indonesia, the new Suharto administration implemented the Foreign Investment Law in 1967 to attract business to Indonesia’s faltering economy, and Freeport-McMoRan was perfect for the deal. The deal was seen as illegal by West Papuans because at that point they were not legally or politically a part of Indonesia at that time. They set up the Grasberg mine near the Puncak Jaya mountain range. It is situated in an altitude of 14,000 feet in a highly remote environment, where a 116km road, pipeline, port, airstrip, powerplant and a town called Tembagapura (copper town in Indonesian) were built.

At the Grasberg mine, the crater like mile-wide open-pit mine is the most eye-catching feature. The pit is surrounded by underground mines and four concentrators. Ore is crushed at the mine and then sent to the mill complex for more crushing, grinding, and flotation used to separate copper and gold concentrates from the ore. From there, the concentrate is transported over 70 miles to a seaport where it is further filtered and dried and shipped all across the world. The tailings (materials left over from the separation process) total over 700,000 tones per day. They are washed into the Ajikwa riverine system, which flush into the Arafura Sea. Unlike other goldmines, the Grasberg mine did not have a tailing dump where the tailings could be treated before they were disposed. The mine officially opened for business in 1973, the operation has more or less been ongoing for 50 years.

The tailings have huge impacts for the environment and the people there. 50 years of dumping has destroyed the nearby sago forests and the aquatic life in the rivers that the native people have depended on for centuries. Representatives over at Freeport says that the tailings don’t contain toxic chemicals, but reports of health problems from local communities in the area have clearly indicated that the wastes they are exposed to include chemicals like mercury and cyanide. Additionally, the water changes to a cloudy black-green color, and many parts of the river system experience sedimentation, causing trees to dry up and fish die off in the thousands due to lack of oxygen. Freeport McMoRan has claimed they will use the waste for road construction, but no roads have been built out of waste.

The Ajikwa River flows through three districts, each with their own indigenous people that no longer have the ability for river transportation routes due to sedimentation. Their hunting, fishing, harvesting, and traveling has been drastically disrupted over time, with the river being a staple for their diet and way of life. According to a report by the UN, the Kamoro and Sempan tribes who live along the river are on the verge of extinction. They have to travel many miles more to hunt for animals or harvest sago, a staple food for many in New Guinea. Those who are exposed to the polluted water develop permanent sores like ulcers on their skin that spread across their body. The sores permeate the skin pigment and wear away the outer most layers of skin. The loss of sea transportation routes means that many have lost access to the few public services in the costal areas, including healthcare and education.

Of course, Freeport tries to paint itself as a company that is committed to sustainability and investing back into the communities they associate with. They pick a select few villages along the costal areas where they provide basic services, but are neglectful of many of the community along the river system. To address them would only open up the Pandora’s box of problems they have created through their mining operations. Today, Grasberg is the largest goldmine in the world, and also the 3rd largest copper deposit, and Freeport-McMoRan is the largest taxpayer to the Indonesian government. This makes any Papuan movement of self determination tremendously more difficult. The Indonesian government, a majority shareholder in the mine, does not have the capital to continue mining operations on their own, and they have a huge financial incentive to keep the Papuan people divided and suppressed. Also, they are incentivized to ignore the grave environmental damages that the Grasberg mine has incurred, much like the palm oil harvesting that that has destroyed many Indonesian forests. Papua, one of the most beautiful and biodiverse oases on the planet, has become a target of colonization and cooperate exploitation through its own abundance.

The Free Papua Movement

When accessing the damage that Papau’s subjugation has had on the land, it goes well beyond the areas effected by the Grasberg mine. Papua is the poorest province in Indonesia. 28% of people live below the poverty line and with some of the worst infant mortality and literacy rates in Asia. Since the Suharto dictatorship annexed the region in 1969, it is estimated that 500,000 West Papuans have died in their fight for self rule. A fact-finding mission has described the situation in West Papua as a slow motion genocide. They have been subject to decades military and police intimidation, beatings, torture, kidnapping, and murder, with no signs of the dire human rights situation improving.

For foreigners, traveling to West Papua is difficult, and local and foreign journalists are frequently detained, beaten and charged on false charges. In recent decades, foreign correspondents wanting to report on Papua had to apply for access through an interagency supervised by the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which acts as a gatekeeper for journalists entering the region. At times, the process has operated as a ban on foreign media. The government in recent years has eases some restrictions, but even to this day getting researchers or journalists to the West Papua region is extremely difficult. Considering that West Papua occupies almost 50% of the 2nd largest island in the world, the media blackout that takes place there is remarkable.

There exists today a secession movement that seeks to reclaim sovereignty for Papuans. The struggle to govern their own land has been ongoing since Dutch colonization, and have shifted towards fighting from Indonesian control since their short-lived independence was taken away in the early 1960s. The Morning Star flag from that time is the official symbol of the Free West Papua movement. The secession movement has gained little traction in Indonesia, so activists are left to plea to international human rights organizations and foreign governments. Across the world, Papuan activists have sought to raise awareness about their cause, advocate for international support, and highlight blatant human rights abuses. The response has been mixed. Some have voiced concerned about destabilization in the region and talk about Indonesia’s “territorial integrity”. While at other times human rights organizations and activists have expressed support for Papuan self-determination. Overall, the hurdles to overcome for doing anything about it are large, and it would take a massive wave of foreign interest to budge the Indonesian government or the Freeport-McMoRan company to change their ways. A literally $100 billion dollar goldmine stands in their way.

So that’s the story. The million people of West Papua live in one of the most ecologically rich and biodiverse places on the planet, have deep cultural ties to the land, and are being slowly eradicated out of existence. They are among the poorest in a country of 220 million. Meanwhile, they live on an island with the largest goldmine in the world, an extravagant wealth which has only subjugated them to colonial oppression. I encourage anyone who is finding out about this issue for the first time to check out some of the Free West Papua movement or the United Liberation Movement for West Papua. Awareness is obviously a key step in the process of liberating the West Papuan people, and I hope that in my lifetime we can see steps taken towards that cause.

If you enjoyed the read, I would greatly appreciate if you subscribed to a monthly/yearly pledge to support my work, so that I may continue providing you with reports like this one.

Alternatively, you can tip here: Tip Jar