Wagner in Africa: Everywhere, All At Once

Is the US exaggerating Wagner's influence in Sudan as a pretext for more direct engagement?

Since the Sudan civil war broke out last week, all major powers have been publicly signaling for peace and stability in the region. As one cease-fire after another collapses, Sudan has caught the world’s attention as the next nation that has the capacity to fall into chaos similar to the civil wars that overtook Libya and Yemen. As the US, Russia, China, France, and other global powers increase their foreign involvement, regional conflicts become global affairs and fall into larger battles for international power and influence. Particularly, Africa has become a primary front for a new Cold War. The present instability of Sudan creates a window of opportunity for foreign alliances as they compete for credibility, natural resources, and regional influence.

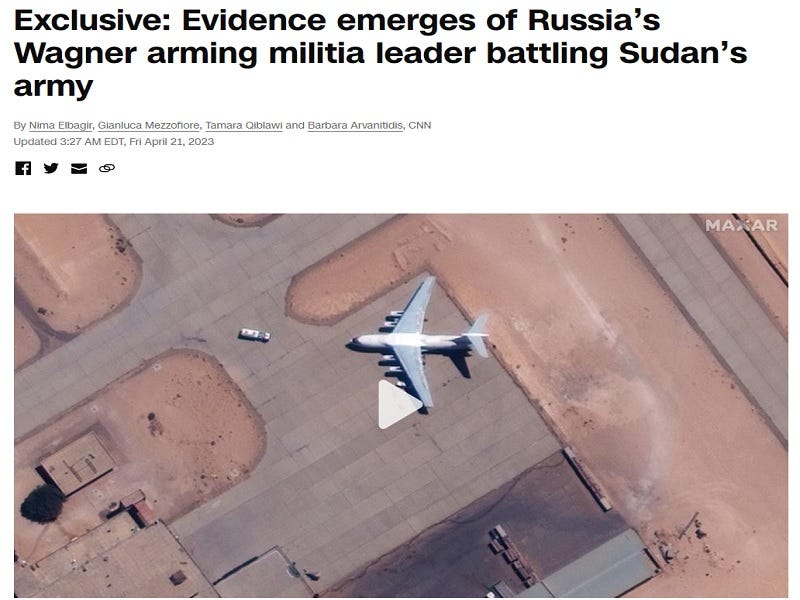

In US media, there is an orchestra of voices talking about a growing influence of Russian paramilitary organization Wagner in the Sudanese conflict, and the “destabilizing” role that Russian influence is playing in Africa at large. CNN’s recent “How Putin’s ‘cat’s paw’ sunk into Sudan” article or the Washington Post’s “Russian mercenaries closely linked with Sudan’s warring generals” show the focus on Russian influence in the region, perhaps signaling for an increasing US presence.

Is Wagner Arming the Sudanese Rebels?

Last Friday, CNN reported that Wagner has been supplying Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) with surface-to-air missiles (SAM) through the Libyan border. The alleged support would be to aid the head of the RSF, general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti against the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Sudan’s de facto President, Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. If true, it would solidify Russia’s support for one side of the conflict while most outsiders have remained neutral.

Hemedti, eager about working with the US, has denied claims that Wagner has taken the side of the RSF or is directly involved in the conflict at all:

"I used to have a good relationship with them, but once they were sanctioned, I have personally told Burhan to deal only with the Russian Federation.”

Similarly head of Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin has also denied claims of this alliance, stating on telegram:

“Due to the large number of inquiries from various foreign media about Sudan, most of which are provocative, we consider it necessary to inform everyone that Wagner staff have not been in Sudan for more than two years.”

These denials would seem to be corroborated by the Sudanese Ambassador to Russia, who reaffirmed Russia’s close relationship with Sudan:

“Russia is a friendly country to us so we have been in direct contact with [the] Russian Foreign Ministry since the very beginning of those events last Saturday.”

The comment is notable because the ambassador is representing the officially recognized government of Sudan led by Burhan. Apparently, even the official government of Sudan doesn’t recognize CNN’s investigation claiming that Wagner is arming the opposition. This could be because they want to maintain their good long-standing relations with Russia. More likely, it could be that these claims of Wagner arming the RSF are completely untrue, used by the US to further its own goals of subverting Russian influence in the region.

Washington Concerned About Fading US Influence

If claims about Wagner arming the RSF are untrue or mostly speculation, why might US media outlets be pushing this narrative? The most obvious reason is to discredit Wagner and Russian influence as destabilizing. Wagner’s success on the battlefield in Ukraine as well as a recruiting tool for the Russian war effort has led to Western efforts to depict them as an international criminal organization of ruthless mercenaries. While Prigozhin is offering himself as mediator between warring parties in Sudan for peace negotiations, the allegation of arming and allying with the more colorful, chaotic, general with a checkered past is the most unfavorable light that Western media can plausibly depict the group. If Russian influence could be synonymous with destabilization, the US could push African leaders away from strengthening ties with the Kremlin and leave more opportunity for US influence.

Another reason could be the pretext for more direct engagement from Washington. Before this breakout, the US hadn’t had much of a dog in the fight. The US supported the ousting of long-time foe of the US, former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and supported the efforts of Generals Burhan and Hemedti, but unlike Russia, had no strong economic ties to the nation. However, The Washington Post reported on the leaked pentagon documents revealing the extent of the U.S. State Department’s concern about Wagner’s growing influence in Africa. Perhaps they see Sudan as a Russian investment and are trying to use the political turmoil as an excuse to grow their own presence. The pretext for a troop presence could be the evacuation of US citizens from Sudan. There have been reports that the US is assembling troops in Djibouti for such a scenario, and it could coincide with thwarting Russia’s plans with Sudan to establish a naval base in the Red Sea.

One way Washington officials may seek to to accomplish growing US influence and weakening Russia influence could be hedging their bets on the more established and internationally recognized government of Burhan. Placing the Russians on the side of his enemy could make him distrustful of the Kremlin and force him to take more aggressive measures to oust Hemedti before he grows more powerful from Russian support. Or perhaps Burhan is seen as the more reliable one; Hemedti expressing a “good relationship” with Wagner may have drawn a line in the sand for US officials. Whatever the reason, if they are trying to provoke a reaction by stoking up fears of Russian influence, they could be responsible for a creating a larger humanitarian crisis that they themselves will attempt to mop up.

Russian Influence in Africa: Not Over Or Underestimating

Russian influence in Africa has been growing in recent years, but not to the extent that US intel and media claim as a driving factor behind regional conflict. The recent deal brokered between the Sudanese government and Russia in February was permission to put a naval base on the coast in exchange for military equipment and weaponry. The deal was set for 25 years with the option to extend every ten years, indicating Russia’s desire to create long-term investments in the region. In 2020, a leaked German Foreign Ministry report said that Russians are planning to build military bases in 6 African countries: Central African Republic, Egypt, Eritrea, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Sudan.

But there is more than just military cooperation. It is safe to assume that Russia’s interest in Africa is similar to China’s and the US. On one hand, they seek to counter Western influence in the region by offering partnerships with African countries that are willing to reduce their dependence on Western aid. Some are forced by an unfavorable US policy — decades of sanctions on Sudan by the US have forced the Sudanese to align themselves with Moscow. The increasing influence from Moscow is motivated by the rich amount of natural recourses and growing economies in the region. Wagner’s presence in Sudan has been described by Samuel Ramadi, author of the book Russia in Africa as “primarily aimed at guarding mineral resources, particularly gold mining resources, and acting as a support force for the Bashir government in terms of protecting it from international opposition”.

Russia’s involvement in Africa can be seen as opportunistic, capitalizing on western failures. Often the West has backed unstable or illegitimate governments that have fed narratives undermining their credibility on the world stage. One notable example was Putin’s mention of Libya in his Feb 24th 2022 speech that coincided with the Russian special military operation in Ukraine. Putin referenced the illegal use of military power against Libya that destroyed the state and pushed the country towards a humanitarian crisis, as well as failed US-led interventions in the middle east. Since the Libyan civil war in 2011, Russia, including Wagner, have expended their presence in Libya through creating a deeper relationship with the Libyan President Khalifa Belqasim Haftar.

Overall, while Russia's influence in Africa is not yet on par with that of the US, China, or some European countries, it is growing, and Moscow is likely to continue to seek ways to expand its presence in the region in the coming years. However, they are far from a driving force of instability, and one should not feed into narratives that they are somehow behind every conflict or the destabilization of every country. Claims by such Cold Warriors could only further undermine credibility and detract from the true extent of Russian influence in Africa. But to those who insist on seeing Russian influence around every corner: is Wagner in the room with you right now?

Russia and Wagner are indeed more beneficiaries from instability and Western failure than the cause of it. This pattern is playing out all over Africa.

It has also been suggested that Russia and Wagner are on opposite sides of this conflict, which is possible in this new era where every conflict is strangely compartmentalized into the war where it was taking place.

Apparently Burhan was sending weapons to Ukraine while simultaneously working with Russia to let them build a military base in Sudan. What a world we are now living in.