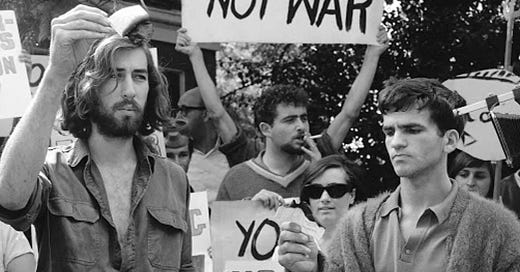

Since we have hardly seen an anti-war movement with any steam since the first leg of the Iraq war, the term is entering again into the wider consciousness as people have had enough of the war machine. The only problem is, it’s been so long, we forgot what it means.

Michael Tracey is not the only detractor to the Rage Against The War Machine Rally, where people are congregating this weekend in the biggest anti-war event of the past decade to voice their opposition to the U.S. war effort.

”I'm pointing out that organizers of a rally billed as "anti-war" have been elevating and publicizing avowed pro-war advocates as representative of their purported cause,” Michael says. He recently agreed to debate Jackson Hinkle, speaker at the rally and blatant Russian supporter, over the question: Is supporting Russia anti-war?

To be clear, Hinkle is one of a minority of speakers at the rally that supports the Russian war goals. Other people have condemned the Russian invasion as an unnecessary act of war. What unites all of the speakers at the event is the end for American intervention to drum up its own war effort.

During the debate, Hinkle was quick to list reasons why he believes the invasion was justified, why Russia didn’t start the war, and he attempts to assert his dominance on the topic. Tracey purported that it does not matter whether or not Russia’s special military operation was justified (and it may very well be), and that applying a military solution in any case is inherently pro-war.

The debate went on and it devolved into insults and people talking over each other. But I had a warm feeling in my heart. The kids are once again talking about being anti-war!

It occurred to me the term fits in well with the other contested definitions and purity tests of different political philosophies—where we fight over the difference between socialism and communism, liberalism and progressivism, libertarianism and anarchism, and right there with the rest: pro-war and anti-war.

These words, used to represent models of societal structures and complex systems, can only exist with flexibly defined application. We will never stop arguing about what they mean, nor should we.

After all, to the people debating the subject, being the one that’s actually advocating for long-term peace and an end to violence means something more than the title of being anti-war. We hold the positions we hold because we think they are best for the world. Alienating your counterpart through accusations of ideological impurity is counterintuitive to the cause itself (No True Scotsman fallacy).

And that’s where the models that we fit into these words fall apart. A woman defending herself against an attacker can partake in her own violence, but it is violence of a different category. It is not violence or anti-violence, but some third thing.

That calls into debate: anti-war from whose perspective? It is believed that Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman’s terror and ransacking of the Confederate controlled Georgia brought a quicker end to the war, saving lives in the process. Or that the dropping of the atom-bomb on Imperial Japan saved droves of American lives from a pending invasion. If we can end the war, through war, is that still the anti-war position? Or are we allowing the anti-war movement to be co-opted by pro-war advocates?

I’ll repeat the question: from whose perspective?

The most important anti-war position to take is the one that applies to the government who controls the ground you are standing on.

As a U.S. citizen attending a rally at the U.S. capital, I am not concerned with which side Russo-Ukraine conflict Americans are rooting for. I don’t care if the event is full of Putin bootlickers or Zelensky fanboys. As long as they are against the 100 billion dollars of foreign aid, are interested in our leaders as a global superpower pushing for peace, or advocate for any of the very sensible anti-war demands listed by the rally, there’s no good reason not to stand next to them, and call for the United States to get its hands out of international affairs and focused on the many domestic crises that face us today.

We can debate about the finer points of civilization later: we don’t want to start World War III. We don’t want more Russians and Ukrainians being senselessly killed. We don’t want a hot war with Russia.

If you agree, then we are diddling around while Rome burns.

It's an interesting perspective, and thought provoking for sure.

On other platforms, I often discuss how propaganda operates and what authoritarianism does to a population. Putin fits the bill for an authoritarian leader, and the propaganda mill he has running for him is incredible.

As such, my usual thought process stops at "Putin's attack on Ukraine is unnecessary and harmful to both his own people and Ukraine, and to the world as a whole due to the typical costs of war."

In my logic, putting a stop to the war would be most beneficial. But you can't effectively prevent further harm so long as an authoritarian regime remains in power. I don't like suggesting war as an answer to anything, I prefer solutions that minimize harm.

But I also can't ignore the fact that some governments are not legitimate. And when they're oppressing and tormenting their own citizens...I don't know what to do about it.

So yes, I would prefer to see world leaders work towards improving the lives of their people and coming together to solve global issues. But how do we do that without addressing tyranny? Or, how *can* we address tyranny in a way that doesn't lead to further death and destruction?

I don't have an answer for that.