Will Washington Accept the "Rule of Law" In Pakistan?

US Officials have every reason to want Imran Khan out of power. Will they stick to their rhetoric of promoting democracy when Pakistan goes authoritarian?

“Don’t look down on anyone unless you are helping them up.” – Pakistan Proverb

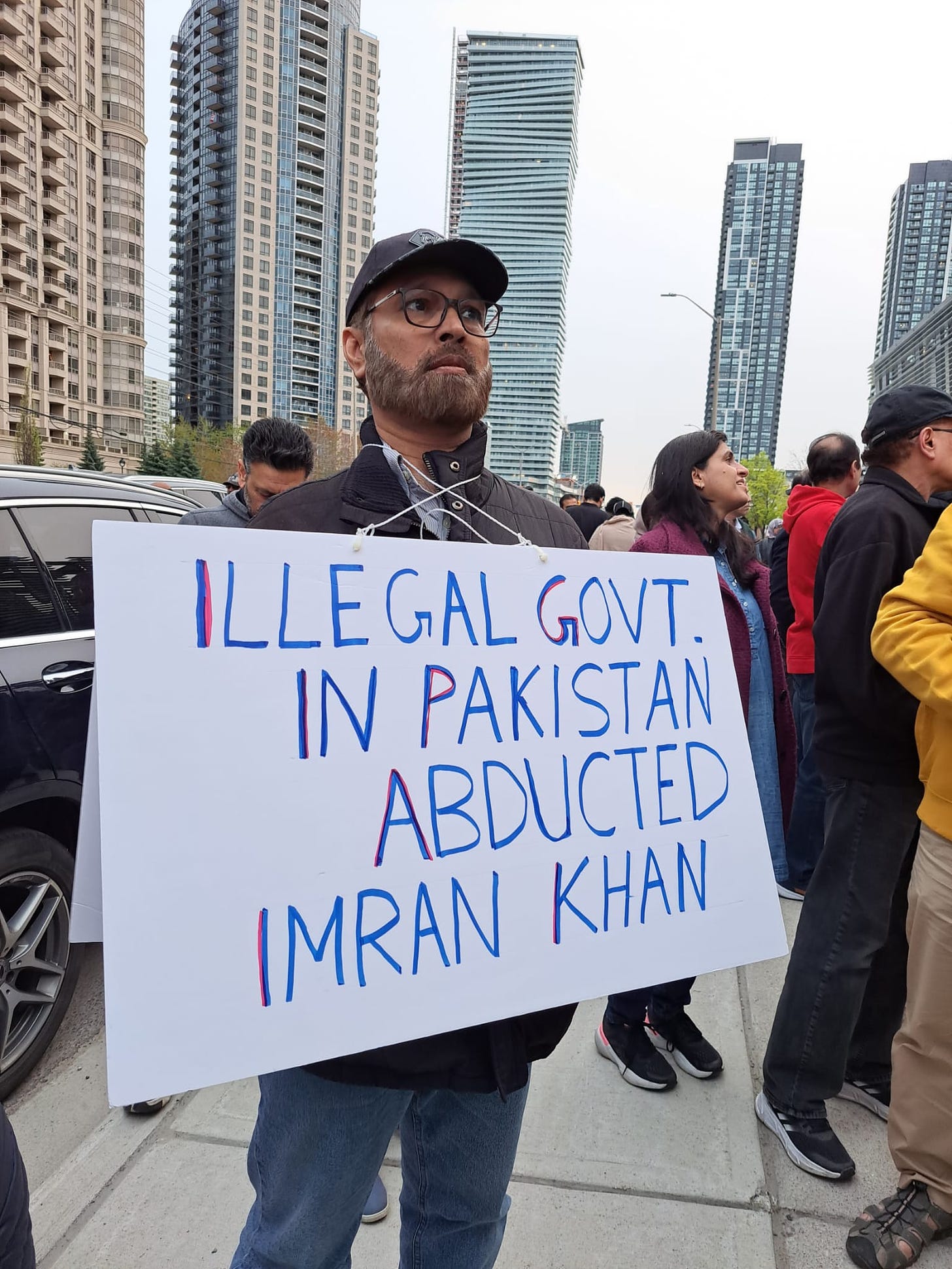

The arrest and subsequent release of former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan has plunged the nation into a state of heightened instability and has created an impasse for democracy through Pakistan imposing de facto martial law. As the regime under Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif arrests opposition leaders, uses excessive force to break up protests, suspends mobile internet services, Western media outlets have largely been hesitant to taking sides in the conflict or condemning these reactions. In the US, Washington officials repeated their usual phrases of supporting democracy and urging Pakistan to support the “rule of law” but expressed no specific concerns about the measures taken by the ruling party to silence dissent. In reality, Washington officials have reasons to ignore Pakistan’s latest authoritarian measures. Khan is an outspoken critic of US foreign policy, embodying the long-held anti-American sentiments held among Pakistanis, and has gone so far as to say that his ousting in 2022 was due to a US-led coup. He is openly multi-polar in the way he conducts politics, and while not hostile to Western cooperation, he proves to be a force of his own. By all measures, he is in the lead to win the 2023 October elections and regain a seat at the head of Pakistan’s government. Khan’s widespread popularity should be a signal to the United States and its NATO allies that neglecting the wounds that Pakistanis have will not just heal in time, they have to address them directly. Furthermore, I’ll argue that Washington is on a foolish path to let US-Pakistan relations deteriorate. If done correctly, the relationship is immensely important for US interests and favorable to the world at large.

The US-Pakistan Relationship: Brief Overview

Whether it was the Cold War, the war on terror, or trying to gain an edge over China, the primary reason for the highs and lows in US-Pakistan relations lies in the US viewing its relationship with Pakistan as a pawn to play in a larger geopolitical game rather than pursuing relations with the country for its own sake. Many times, Pakistan had been a willing participant, recognizing the benefits of aligning with the US for military and economic assistance, or as a counter to the USSR's close relationship with India. When the United States would accomplish its goals through cooperating with Pakistan, the relations would usually break down again. It has been a relationship entirely contingent on mutual interests, with little regard for any long-lasting relationship.

Wedged in between India and Afghanistan, both of which received support from the Soviets, the US saw the capitalist country of Pakistan as a natural strategic ally in the Cold War. The 1954 Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement was the first major step in securing Pakistan as a military ally when the US was looking for a strategic alliance of Asian states to deter the expansion of communist influence. The agreement provided over $3 billion in military and economic aid. At this time, relations between Pakistan and the United States were at an all-time high. "Our army can be your army if you want us," President Ayub Khan told the Americans in 1954. In the end, the US support for Pakistan's army contributed to the military domination of Pakistani politics that would follow in the coming decades.

Although Pakistan was willing to fight for the United States in its battles against communism, Washington would never substantially help Pakistan in its security threats. The Sino-Indian War of 1962 resulted in India's defeat to the Chinese, and the United States shipped arms to India, without considering if those arms would be used against Pakistan. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 saw United States weapons used against India, and as a result, the US imposed its first sanctions on Pakistan later that year. Both India and Pakistan felt betrayed by the US for its lack of support in the conflict.

The other defining factor is Pakistan’s nuclear program. The US has subjected Pakistan to unilateral sanctions several times over Pakistan’s nuclear ambitions. Pakistan first established a nuclear energy program in the 1950s, and soon after, India started to build a nuclear weapons program. Many in Pakistan found it necessary to follow suit for national survival. President and Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto once said about Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program: "even if we have to eat grass, we will make a nuclear bomb. We have no other choice." In 1974, Pakistan carried out its first nuclear test, which concerned the whole international community about a nuclear conflict between India and Pakistan. In 1979, the US imposed sanctions under the Symington Amendment and the Glenn Amendment, which prohibited giving assistance to countries that have nuclear enrichment technology without first agreeing to international safeguards and inspections.

The sanctions were short-lived; however, the CIA underwent Operation Cyclone to arm the Mujahideen in Afghanistan with close cooperation from the Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the equivalent of the CIA. The long and arduous mission is infamous for bringing about the rise of Al-Qaeda, but the cooperation with Pakistan has largely been overlooked. Through the ISI, jihadist groups that would fight the Soviets in Afghanistan were partly trained, equipped, and originated in Pakistan. The program was ultimately successful in weakening the Soviet efforts in Afghanistan and played a big role in the collapse of the USSR.

In the 1990s, the United States again imposed economic sanctions on Pakistan over its nuclear program. However, after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the United States once again turned to Pakistan as a key ally, this time in the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan. The United States provided significant military and economic aid to Pakistan in exchange for its cooperation in the war on terror. At the onset of Washington’s war, Pakistan agreed to play the middleman and supported the US in conducting their operations in Afghanistan. The US military had unfettered access to Pakistani territory, allowing the US military to use its airbases and supply routes, and Pakistan’s military would supply the US with intelligence about the Taliban and al-Qaeda militants. Pakistan would even capture key al-Qaeda terrorists for the US.

But when US drone attacks would be used on Pakistani soil, the Pakistani people held a constant fear of being struck, and this became a huge source of anti-American sentiment in Pakistan. At one point after a US/NATO manned air strike killed three Pakistani soldiers, they responded by cutting off a vital supply route into Afghanistan. Questionable practices of using Pakistan for the war on terror got even worse when the CIA collaborated with Pakistani doctor to set up a fake immunization campaign in Abbottabad so he could collect DNA samples in hopes that they would find the DNA of Bin Laden. When the news broke, it eroded the trust that communities had in immunization programs that took years to repair. Anti-American sentiment was at an all-time high and it would be reflected in Pakistani politics with the rise of a nationalist, outspoken critic of the war on terror Imran Khan.

Imran Khan’s Resistance

While the odds of being struck by lightning are low, the chances of lightning striking the same place twice are at least twice as high. Imran Khan's unrivaled success as a cricket player and a politician has been lightning striking twice. There have been notable people in the past half-century who have become political leaders—Arnold Schwarzenegger, a bodybuilder who moved and finessed his way into becoming the governor of California, and Manny Pacquiao, a world champion boxer turned senator in the Philippines. However, Imran Khan stands entirely in a league of his own. He is considered one of the best all-around cricket players of all time and one of the greatest cricket captains, leading his team to victory in the World Cup in 1992. At that point, he could have retired as a wealthy world-class athlete and lived a life of luxury. Instead, he transformed his own political party, which started as a seemingly insignificant political gesture by a celebrity, into what is now the most popular party in contemporary Pakistan.

Khan founded the party Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), which translates to "Movement for Justice," in 1996. He believed he could use his career as a famous cricketer and philanthropist to build a political movement. He was right, although it had a slow start at first. Critics called his plight "a party of one," but over a decade, he began gaining political traction. The party was designed by Khan as an anti-corruption party, fighting for social justice and liberal values, but it remained insignificant for several years. On their website, it says, "One of the initial goals of PTI was to make our justice system independent so that all countrymen, be it rich or poor, can get the same level of justice." In 2002, Khan won a single seat in the 342-member Pakistan National Assembly. The party would not win another seat until the 2013 general election. This was partly because, in 2008, PTI, along with five other political parties, decided to boycott the general elections due to concerns that they were rigged in favor of the ruling party, the Pakistan People's Party (PPP). Khan increasingly opposed military rule in Pakistan.

The PTI staged a number of high-profile protests and rallies in Pakistan regarding the corruption, and in the run-up to the 2013 general elections became one of the most popular political figures in the country. He centered his campaign around uprooting Pakistan’s corruption within 90 days of his tenure, establishing an Islamic welfare state, and ending the country’s involvement in the war on terror, which he was deeply critical of. He was an outspoken critic of US foreign policy in his home country over the enormous cost that it had on Pakistan:

"According to the government economic survey in Pakistan, $70bn has been lost to the economy because of this war. Total aid has been barely $20bn. Aid has gone to the ruling elite, while the people have lost $70bn. We have lost 35,000 lives and as many maimed – and then to be said to be complicit. The shame of it!"

This shame was shared by many in Pakistan when, in 2011, it was America and not Pakistan that announced the death of Osama bin Laden at the hands of US commandos. Meanwhile, CIA Director Leon Panetta told Congress that the Pakistani government was "either involved or complicit" in Bin Laden hiding out in a town 35 miles away from Islamabad. While Americans were feeling a sense of jubilation over Bin Laden's death, the affair was embarrassing for Pakistan. At that time, Imran Khan was in a perfect position as a well-spoken and already well-known figure to criticize his country's ruling party, the military, and Pakistan's support for the disastrous US war in Afghanistan. In many ways, he embodied the anti-American sentiment shared by Pakistanis and the anti-status quo movement that was erupting during the Arab Spring. In the 2013 general election, he came second in the race for Prime Minister, and his party won 35 seats in the National Assembly. He continued to claim that the elections in Pakistan lacked fairness and transparency, a sentiment often expressed in nearly every election in Pakistan, suggesting that he was even more popular than the election results indicated. In the aftermath, the PTI staged numerous protests and rallies, demanding a re-election and investigation into the fraud.

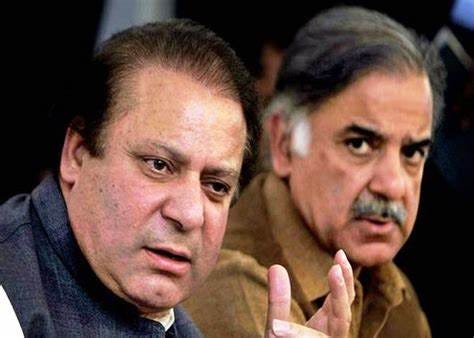

Khan's rise can be attributed not only to his own success but also to the failure of his political contemporaries in handling accusations of corruption and foreign meddling, particularly from the US. The release of the Panama Papers in 2016 revealed that the then-incumbent Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, had millions of dollars of overseas property and was found guilty of corruption charges. Sharif was subsequently removed from office, and the Supreme Court of Pakistan ruled that he was disqualified from running for public office ever again.

Khan, now in his 60s, did not fade away after successfully establishing the party. Instead, he grew even more popular. In the 2018 general election, he emerged victorious and became the Prime Minister, referring to the elections as the "cleanest in Pakistan's history." True to his promise, he made efforts to crack down on government corruption. He established the National Accountability Bureau, an organization tasked with investigating and prosecuting corruption cases. Additionally, he worked towards curbing the practice of holding property under someone else's name to evade taxes and launder money, similar to what happened with former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

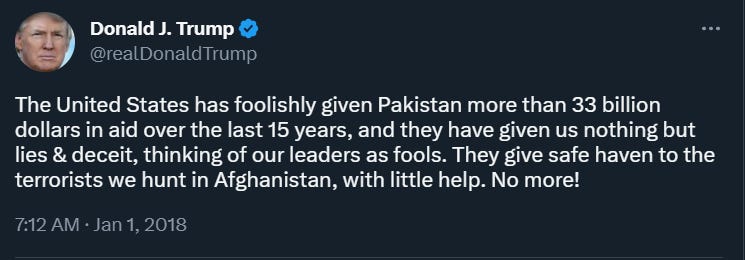

During his tenure, Khan never displayed open hostility towards the United States but instead exercised great restraint to avoid repeating the same mistakes Pakistan made in its support for the war on terror. He maintained a mostly positive relationship with President Trump and effectively utilized his connections with both the Taliban and the US to negotiate a withdrawal deal in 2021. Prior to Khan, Trump had a strained relationship with the Pakistani government:

He refused to meet the CIA director William Burns after he visited Pakistan without first scheduling a meeting, saying he does not have free rein to come unannounced. He said he would absolutely not allow the CIA to have bases in Pakistan for launching attacks against Afghanistan. Khan’s refusal to cooperate with the US war in Afghanistan alone was not enough to give Washington the assumption that he was anti-US in a broader sense, but it became increasingly clear that he was not subservient to US/NATO pressure. During the start of the Russian invasion in Ukraine in February of 2022, Khan was in Moscow meeting with Putin at the time. A meeting that Washington had asked him to cancel, which he denied. He refused to condemn the invasion, despite pressure from the heads of 22 diplomatic missions, mostly countries from the European Union, asking them if they thought Pakistan was their “slave”. He also refused to join the consortium of sanctions that had been imposed on Russia.

This coincided with a degrading relationship between Khan and the military. Pakistan military leaders started easing its grip on opposition parties which led to the no-confidence motion in April 2022 that ousted Khan from office. Khan lost his majority in Parliament by 2 votes. He started making familiar claims of foreign interference and corruption in the electoral process. This time though, he said that he was overthrown in a US-led coup to remove him, a claim he was making even before the results of the no-confidence vote came. The basis of these claims stems from US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Donald Lu allegedly threatening Pakistan's former ambassador to the US, stating that if they do not remove Khan through a no-confidence vote, Pakistan would face consequences. There were also reports that opponents of the PTI were frequenting the US embassy. While it would only take a few defectors to shift the narrow majority in parliament against Khan, there is no smoking gun that indicts the United States in a coordinated attempt to oust him. However, it is seemingly convenient for the United States that Khan would be removed, and the idea remained very popular among his supporters.

So popular, that When Khan was arrested on corruption charges, many accused Washington officials or the CIA of being behind the arrest. Khan’s supporters have framed his leadership role in Pakistani politics as one of a patriot versus dissenters, integrity versus corruption, national influence promoted by popular sovereignty versus those sold out to foreign special interests. It is reminiscent of ardent supporters of Donald Trump who view him as a bold celebrity figure constantly battling against the 'deep state' in his home country, while opposition parties strongly desire to see him out of office.

Now that the Supreme Court of Pakistan has ruled his arrest illegal, Khan is more popular than ever. It looks in all likely that the 2023 elections would be a landslide for Khan as long as he is not disqualified by some legal roadblock. US spokesmen have claimed that they don’t have a preference for who is ruling Pakistan, and want to support free and fair elections, but have conveniently spoken nothing about Pakistan leadership throttling internet access, arresting journalists, or Khan’s illegal arrest. If they were truly impartial advocates of democracy, they would not be silent on such matters. Now, in lieu of his growing popularity, the US/NATO alliance may have to again reconcile with a Pakistan and a leader that is so comfortable with multipolarity, and considerably more cajónes to stand up to Western-backed influence than the Sharif’s political dynasty. But the shift towards multipolarity is bigger than Khan in Pakistan, he is merely the leading figure, and whether or not he wins the election this October, the large constituency that he and the PTI party represent will play out for decades in Pakistan and continue to have an effect on US-Pakistan relations.

Massive Incentive for US involvement

Despite the past and present turbulence, it is hard to imagine what the past half- century would look like without US-Pakistan cooperation. For better or for worse, when the US and Pakistan work together, they shape the world. These examples come to mind:

If Pakistan had never been a willing participant in Operation Cyclone, the war of attrition against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan might have not been possible, an operation that greatly contributed to the bankruptcy of the USSR.

The US has made successful efforts to defuse tensions and prevent conflicts between Pakistan and India, one notable instance was during the Kargil War in 1999, a border dispute in the Kashmir region that had the potential to escalate to a nuclear exchange.

Although many hawkish officials in Washington try to frame Pakistan as indifferent or complicit, its support was crucial for the US war in Afghanistan, and without it, the US may not have been able to attempt their 20-year failed government-building endeavor in the country. Without Pakistan’s cooperation, Afghanistan may look totally different today.

The US has a huge incentive for truly respecting a democratic process in Pakistan and maintaining a relationship with its leadership. One that, as writer Madiha Afzal from the Brookings Institute points out that a relationship with Pakistan “ought to be seen by the United States on its own terms and not through the prism of its neighbors.” The US has long been Pakistan’s largest export market, and with 230 million people, Pakistan is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

The current shift away from Pakistan in Washington is evidence that they undervalue the country for what it offers to the United States, the world at large, and the US’s position in the world at large. Trump had met with Khan several times, but Biden had not called him the entire time he was in office. It seems that the Biden administration, like many previous administrations, has chosen to discard their relationship with Pakistan when their interests no longer align, which resets the efforts to restart relations back to square one. Last October, Biden seemingly had one of his old man gaffes talking about China and threw Pakistan’s name under the bus in an incoherent statement:

This is a guy [Xi Jinping] who understands what he wants but has an enormous, enormous array of problems. How do we handle that? How do we handle that relative to what’s going on in Russia? And what I think is maybe one of the most dangerous nations in the world: Pakistan. Nuclear weapons without any cohesion.

While Biden has not offered any diplomatic solutions for dealing with Pakistan as a place with “nuclear weapons without any cohesion”, his administration had offered a $500k grant for teachers in Pakistan to teach English, including a sizable portion of that for transgender youth. This has been the most popular story regarding America’s relationship with Pakistan during the Biden administration. A great way to win over the people of Pakistan (sarcasm).

If relations were to further break down leaders could be incentivized to trade even more with competitors of the US. China has made huge investments in the country in the past decade, with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is the largest infrastructure project by China in any foreign country. It includes massive investments in transportation infrastructure, energy projects and economic zones for future investment. If the US continues its past policy of sanctions to punish the Pakistan government while China is making long-term investments in the country, the economic factors swaying the relations away from the US would be too large to shift. The chance to provide an economic alternative to China may be soon fading away permanently.

To isolate Pakistan due to its multipolarity, or to be silent over authoritarian measures when it works in favor of a more western-friendly candidate, could deteriorate US-Pakistan relations to a new low — one that could have huge implications for United States leverage in South Asia and the Middle East. As the US struggles to remain as relevant in these regions, while they no longer have the same hegemony they enjoyed in the past decades, they ought to hang onto whatever relationship they could salvage with the Pakistani leadership and people. It should be noted that relations between India and the United States improved after the 1999 Kargil War when the US leveraged its relationship with Pakistan to deescalate the conflict. Additionally,a nuclear war between Pakistan and India has the potential to plunge the world into a nuclear winter — the United States would benefit as a global superpower to have some influence in the conflict.

As far as healing the wounds between the Pakistani people and the US from the war on terror, the cold shoulder approach of the Biden administration only fuels anti-American sentiment in the country. A sentiment is important for Americans to understand and not just use as an attack vector on Pakistan. Imran Khan is justified in expressing regret over his countries’ participation in the war on terror. If our leaders had remorse, they’d have apologized for America’s role in destabilizing Pakistan in the war on terror and set up some charity fund for Pakistan drone victims instead of largely ignoring the issue as previous administrations have. If Pakistan does have a better relationship with the Taliban, that position should be leveraged and not condemned as morally defunct. They should share some credit for ending US involvement with the Taliban by using that leverage, instead they were not mentioned during the withdrawal from Afghanistan and have been an afterthought since then.

Similarly, if Pakistan is not as quick as the EU to align with the wishes of the US and NATO, that alone is not a sufficient reason to let relations deteriorate. Pakistan faces pressure from its alliances to act differently, which provides valid grounds for being distrustful of Western war narratives. In truth, they have fewer reasons not to trust Americans than we do them. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2012, only 10 percent of US respondents felt that the United States could trust Pakistan, while only 11 percent of Pakistani respondents had a favorable opinion of the United States. This sentiment can be attributed to cultural differences, but it is likely that actual US foreign policy towards Pakistan also significantly influences these perceptions. The same policies that have fueled concerns about immunization programs, or the US being involved in a coup to overthrow the most popular figure in Pakistani politics. The hyped-up fears start from a legitimate place.

A reset is desperately needed in US-Pakistan relations, as it would be mutually beneficial for both countries and the world as a whole to improve relations between the 3rd and 5th most populated countries on the planet. To make this happen, US officials must accurately assess the current climate of instability in Pakistan and actively work towards promoting democracy, going beyond mere vague and empty statements. The US should aim to positively influence Pakistan's electoral process by not engaging in direct interference but by speaking out against anti-democratic actions whenever they occur, especially when they involve Pakistan's most popular political figure. The need to recognize that Khan’s ideas and his PTI party is the most popular in Pakistan and rehabilitating its image to their movement and the people of Pakistan at large is a worthwhile and underrealized priority.

If you enjoyed the read, I would greatly appreciate if you subscribed to a monthly/yearly pledge to support my work, so that I may continue providing you with reports like this one.

Alternatively, you can tip here: Tip Jar

Great piece.